This article is written by Sara Do, Cultural Infusion’s Research and Project Coordinator Intern. Sara has a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Studio Art and currently doing her Master of Arts in Cultural Heritage and Sustainability. She is currently writing her Master’s thesis on the definition of sustainability in sustainable art. As an ICI herself, she is interested in how the intercultural community such as TCKs can be included in the Heritage discourse.

Have you ever asked yourself “Where home is?”, “Where do I belong?” or “What’s my heritage?” You are not alone. In this globalised world, approximately 220 million children have lived in a country that is not native to their parents and have all asked a similar question (Iyer 2013). This group of people are named Third Culture Kids (TCKs), a term created by Ruth Hill and John Useem during their ethnographic study of expatriate communities in India in 1967.

Who are Third culture kids (TCKs)?

TCKs is a general term to describe children who spent a significant amount of their developmental years outside of their parents’ or their own passport country. They are the children who created their own culture, the Third culture. Out of their parents’ culture, the first culture and their host country’s culture, the second culture. TCKs experience estrangement because of their constant transition between different cultures and countries. Due to that, they don’t identify with a singular culture causing disconnection with World heritage. Researchers are now redefining the term TCKs after realizing that the group does not stay within the traditional frame of culture.

What are the types of TCKs?

Some traditional TCKs can be:

– Military Brats: Children of those that serve the military and moved internationally.

– Missionary’s kids: Children of those sent on a religious mission

– Diplomat kids: Children of ambassadors and others engaged in diplomacy

– International business kids: Children of those who work for multinational corporations

What are the possible lifestyles/behaviours of adult TCKs?

According to research on the culture of adult TCKs, there are several paths TCKs tend to follow and adopt a specific lifestyle or behaviour as an adult TCK (D.U.S 2018).

TCKs may reflect on only one of the cultures they encountered to find a set identity to live with. For example, military brats tend to live on the military base so they may experience a controlled environment of culture in this environment.

They may reject the identity associated with their passport country so that they can identify with other cultures better. For example, TCKs who live in a neighbourhood with a dense local population may experience stronger otherness and absorb the local culture/behaviour faster to fit in.

People may constantly code-switch to fit in with others. For example, missionary kids who have expected behaviour by their religion may change their behaviour/vocabulary when talking to different people.

Some may accept that their permanent identity as being different from others. Moreover, they may retain elements of each culture, blending them into a unique personal identity, which would be the one that best explains the definition of the TCK.

TCKs experience constant change in the environment and people they associate with. Therefore, they tend to go through withdrawal patterns, such as avoiding deep engagement with others, spending excessive time alone, remaining an outsider and observing rather than getting involved to avoid being exposed as someone who doesn’t know the local culture or going through the pain of losing someone again.

So what is TCK heritage? How can people who don’t live together have the same heritage?

TCKs’ lack of attachment to the concept of “home” or “place” tends to cause a lack of connection to national or tangible heritage. According to research on relevant TCK heritage, TCKs consider objects related to travel for example, their passport, visa, currency and their education, i.e. IB exams, A level exams, as their heritage (Colomer 2017). When it comes to intangible heritage, they connect with the idea of family, language, homelessness or feeling at home everywhere. From this research, we can tell that TCKs tend to feel more connected to thoughts and emotions unrelated to a physical location.

What are the problems with the term TCKs?

The term TCK has helped people understand their lifestyle, find their community and help researchers understand their behaviour. The research by Ruth Hill and John Useem focuses on the cross-cultural relationship between two countries. Therefore, it does not consider other types of TCKs nor how global interconnectedness affects the following generations. Even traditional TCKs, such as missionary kids and ambassador kids, tend to move around more than two countries. According to this study, they experience more intercultural identity development than the term TCK suggests (Karim Rangoonwala 2019).

The term ‘third culture’ also divides individuals from others, creating estrangement which does not reflect their sentiment of belonging everywhere.

Moreover, the term only focuses on multicultural experiences during their “developmental years” (Pollock et al. 2017, p.26). It does not include other types of multicultural individuals who also experience cultural identity crises and estrangement from different years.

In 2001, after receiving feedback on their first book ‘Third Culture Kids: The Experience of Growing Up Among Worlds’, David Pollock and Ruth Van Reken introduced the updated term Cross-Cultural Kids (CCKs).

Who are Cross-Cultural Kids (CCKs)?

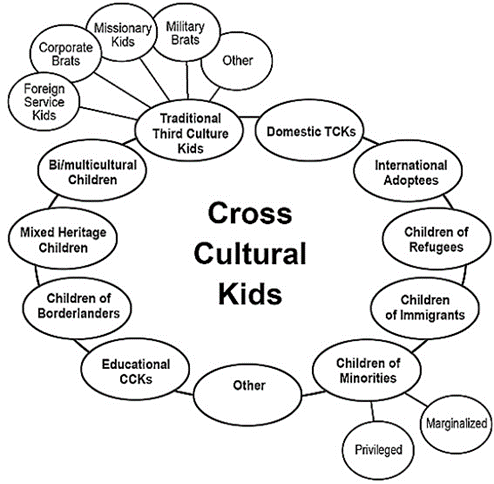

The term CCKs refers to the people who lived in more than two cultural environments during their developmental years. The updated term allows more multicultural individuals into the conversation, which can eliminate the question of “Am I also a TCK?” and allow a greater understanding of their culture and identity. You can also see on the diagram below that this includes immigrant children, adoptees and even minority children:

Intercultural Individuals (ICIs) rather than TCKs or CCKs

The updated term CCKs, cross-cultural suggests that people consider their multiple cultures separately rather than combined as one mixed cultural identity. However, as explained above, many of them use their different cultural backgrounds simultaneously, not separately. Therefore, I suggest Intercultural Individuals (ICIs) as an updated term for this group.

Pollock and Van Reken suggest that the cross-cultural experience must happen during the developmental stage, and that is why the “K” in TCKs and CCKs refer to kids. However, I suggest that it does not have to. People who move during adulthood may also have their cultural identity significantly influenced by this experience. That is, after a considerable period, adults can also experience changes in their language skills, cultural thought processes and understanding of intercultural lifestyles. The distinction between the influence during childhood and adulthood is that greater effort and time to assimilate is required in adulthood rather than in childhood. Pollock and Van Reken (2017, p.26) stated “no one is ever a former third culture kid. TCKs simply move on to being adult third culture kids”. If this is true, why differentiate those groups and not just refer to them as Intercultural Individuals (ICIs)?

However, I am not suggesting getting rid of the previous terms. I am proposing making ICIs the overarching term and TCKs a subgroup. The term TCKs has been the most common way to describe this diverse community and is the most well-known amongst non-scholars compared to the other terms. Moreover, the current definition of TCKs that understands the aspect of continuous movement and expected return to their native country distinguishes TCKs from other intercultural individuals, such as immigrants who plan to stay. Therefore, that while it is important the previous terms are maintained for research purposes and for the general public, I suggest the usage of the term ICIs from now on.

Bibliography

Colomer, L 2017, ‘Heritage on the move. Cross-cultural heritage as a response to globalisation, mobilities and multiple migrations’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, vol. 23, no. 10, pp. 913–927, viewed 5 November 2019, <https://core.ac.uk/display/132353685>.

D.U.S. 2018, The culture of adult third culture kids.

Iyer,P.2013,Whereishome?, https://www.ted.com/talks/pico_iyer_where_is_home/transcript?language=en.

Karim Rangoonwala, M. 2019, ‘Negotiating third culture kid identity gaps: An (inter)cultural communication perspective’, Master’s thesis, California State University, Sacramento.

Pollock, D. Van Reken, R. Pollock, M. 2017, Third culture kids: growing up among worlds. Nicholas Brealey Publishing, Boston.

Share this Post