CEO Peter Mousaferiadis presented the keynote address at the closing of the SIETAR Congress 2020 on 28 November 2020. The theme of the congress “the Future of Inclusion” focused on living and working together, developing collaborative intelligence, global citizenship and getting ready to deal with the economic, climactic, intercultural and inter-religious dialogue and migration challenges facing our world in the future. The aim was to link the latest research with concrete actions, best practices and grassroots initiatives.

Peter joined forces with social activist and international photographer Petar Mitrovic through an interactive activity which utilises byzantine chant and “ONE WORD” call to action to build a world without borders together.

During his keynote, Peter spoke about how the interconnectedness of the information age has introduced a renewed sense of intercultural connectivity between different peoples. He recounted anecdotes about the immigrant experience from his own childhood, discussed the Greco-Hindu-Buddhist origins of the first bilingual coin and also touched upon the controversial artworks of PissChrist and Charlie Hebdo’s cartoon depictions of the Islamic prophet Muhammed.

Introduction, Thanks and Welcome

Thanks for the warm welcome Anne-Claude and Good Evening Everyone from Melbourne Australia, 16,360 kilometers away from Switzerland. In the scheme of the internet and our universe it’s a blip. On behalf of all the delegates and presenters, I’d like to express my wholehearted thanks to the many who have seen to the success of this congress. I can only imagine how many hours, days and months of planning has gone into this conference. A special thanks to the working committee and in particular to Jillaine Farrar and Anne- Claude Lambelet. Thanks for your tireless efforts and your meticulous attention to detail.

All of us come together through a shared interest in human differences and diversity, and the manifestation of this in the countless spaces we all operate in, whether it be in organisations, communities and homes. I’d like us to offer a moment of silence for those who are less fortunate than us and for those who have been affected by the pandemic which is wreaking havoc across the globe.

It is customary in Melbourne, Australia before any official proceedings to always pay homage to the respective custodians of the land. Australia has one of the longest living cultures extending back to more than 70,000 years. Before Europeans arrived in Australia, there were more than 324 distinct people groups. Australia was always an important meeting place and location for events of education, social, sporting, spiritual and cultural significance.

Today, we are coming together just like the past, present and emerging custodians from Melbourne. Custodians who have always had a deep respect and connection to land, water and the communities they represent. I’d like to also pay my respect to any elders and custodians representing first nations who might be present today.

I have been given the task to share with you not one take away but to summarise the conference highlights through a personal narrative that explains my journey into the world of interculturalism. I took the liberty to watch all the presentations and was dwarfed by the wisdom being shared by all the presenters. I came up with over 35 pages of notes summing up every presentation, and over the last 2 days, gave myself the arduous task of weaving everything into a narrative that I hope will do justice to the last 5 weeks.

Today my keynote is titled ‘A light in the Crack” and influenced by the story shared with us by George Simon.

Today, I will be asking you to ponder on some ideas. New and not so new. I am presenting before you not as a son of Greek rural migrants who travelled to Australia for a better life in the 1950’s but rather as a human being who stands in the shadow of a Greek philosopher who lived 2400 years ago in a City on the Black Sea Coast of modern day Turkey known as Sinope.

Thiogenis as they know him in Greek – Diogenes. Diogenes by most people was known as the person who lived in a barrel. Diogenes lived the life of a kin, the ancient greek word for dog which cynicism is derived from, hence, Diogenese the Cynic. Most people don’t know that Diogenese was also the first human being to proclaim “I am a citizen of the world”. The notion of a ‘citizen of the world’ resonates with all of us and postulates that all human beings belong to a global community based on shared morality.

The advent of the World Wide Web (WWW) in 1989 has created a global super-connected age. The ability to navigate our way through how we see the world and how we relate to each other has become central to global citizenship.

I have spent the better part of three decades working as a creative director, music conductor, composer and producer. In 2002, I founded Cultural Infusion as a response to the impact of globalisation on society and as a means to addressing issues of lack of understanding of the other and a way of reducing ethnic and race based discrimination.

Over these three decades, I have come to realise the power of the arts, the power of culture and that as a people we don’t do enough to draw upon humanity’s greatest asset – cultural diversity. Our most recognised brand, yet our most under-utilised brand. I wish to share a story with you about my 93-year-old father. A few years ago, he asked me in Greek:

“Pethi MOU!………………..My Son! I have never quite understood. Tell me, what is it that you actually do?”

“One day you are conducting, the next you are writing music, the next you are directing and producing international events for clients such as the Parliament of World Religions, our Australian Government and the United Nation’s, then I hear you’re developing a winning slogan for a UN campaign.

Then there’s the thousands of education programs you’re delivering. And now, I hear something about digital products and a big data initiative you’re working on which focuses on measuring diversity”.

TELL ME! What is this job. I don’t understand. That was light bulb moment.

I realised everything I did was not because of the actions I was involved with but what drove me. The purpose behind what I did. The WHY. Everything I was involved with, always used arts and culture as a meaningful driver to building intercultural understanding as a core value and key competency of global citizenship.

Here is another anecdote which I believe in many ways sums up the SIETAR 2020 Congress.

There was chicken walking down a six-lane highway. As it was walking down it noticed a chicken on the other side. It screams out, “how do I get to the other side?” The other chicken replied, “You are on the other side”. What this anecdote highlights is not only our curiosity for the other but that we all assume that everyone sits on the other side. The anecdote also illustrates ethnocentric judgements, i.e., how we use our own culture as a reference point in assessing other cultures rather than trying to see it from another viewpoint.

Over the past few weeks, Helen Spencer in her talks emphasised, if you ignore your staff and ignore your people, sooner or later you will lose out. Whatever business you are in, you are only as good as the people you understand. Space and time have become super-compressed in the last decade of our globalised age. A new form of intercultural communication is required which synthesizes these incommensurable cultural differences.

Pia Stalder emphasised the importance of adopting different perspectives. Through the stamp of the Mattahorn Swiss Mountain which can also be seen as the African continent, she reminded us that we need to keep our eyes and ears open with individuals coming from all over the world. The chicken anecdote also highlights that in societies there are rifts, chasms and there are stories that define every single human. Almost 8 billion stories. There are stories within those stories.

MORE THAN ONE STORY is card game inspired by Chichinanda who told a Swedish TV audience that we need to tell more than one story. It’s this story that influenced colleague and friend Seth Selleck to come up with the innovative and globally recognised card game MORE THAN ONE STORY which he shared with us. MORE than One Story has been played by more than 1.2 million people and has gone on to be recognised as a winner of the UNAOC Intercultural Innovation Award.

In the SIETAR 2020 Congress we heard stories from the times of when rocks were first used as tools by humanity to stories of children who recently crossed dangerous seas and today long for a sense of belonging. A home.

Storyteller: Dr Aminata Cairo ‘All stories are valid’

In her impassioned opening, Aminata stated the need to treat all stories as being valid. How do we deal with the tension between the dominant and the other? Aminata says, Diversity is not just about stories and their differences but also the difference in their inherent quality.

Collectively, we have a wealth of stories that we can share with each other. How do we treat each of these stories as equal and how do we deal with the tension at the point of convergence?

I am forever pondering over this point of convergence. Often the unintended consequence of confluence is ethnic and race based discrimination. People say that we need to step up. I say, It’s going to require a monumental almost evolutionary shift in thinking before we can eliminate ethnic & race based discrimination.

All societies resonate with a dimension of history and cultures that allow privileges associated with a hegemony often not afforded to others. Institutions and structures cannot be dismantled overnight. The Future of Inclusion is going to require global efforts to revision our societies so they can become nimble and adapt to the ever changing world we are finding ourselves in. Every one of us here has a role to play.

I come back to the point of confluence which has been a theme running through this conference and how nexus points can not only be turbulent however also a moment of great creativity. Again and again throughout the conference presenters stated that there are endless benefits in embracing the other.

Migration is a loaded word as we heard in the first Unpacking Migration session. Gianni d’Amato, Eugenia Arvanitis and Helen Taylor all highlighted refugees integrated into society creates benefits for all. This is a no brainer to us but how do we communicate this to others who don’t think so.

Refugees are an asset and always have been, yet they forever experience obstacles. The latest research highlights that where migrants are integrated into a society in areas where there is greater diversity, the more positive the outcome. Areas with lowest diversity had the highest negativity towards refugees. In another words, the more pluralistic we make our societies, the more accepting we become of migration and refugees.

Migrants experiencing obstacles in new homelands is not new. I imagine it has been happening ever since the dawn of time.

In the 50s, when my father arrived in Australia he had a moustache. Let me add, not quite like mine. At the movies people would meow, meow, others would give him strange looks and others would make fun of him. One day when he was walking home from the market with a box of grapes he was accosted by three men who for no reason surrounded him, poked at him, made fun of him, pulled on his moustache and beat him. I asked my father. Why did you not react? Well firstly, there were three of them. What chance did I have? Did you feel angry afterwards Dad? No, I felt pity for them.

As humans, we need to express compassion and forgiveness, and where possible engage in meaningful conversation. This is a theme that has also come up in the congress and one I entirely agree with. Compassion.

In the third session of Unpacking Migration, key areas highlighted what we can do for migrants & refugees to assist with making them feel included in our societies. Things such as:

- Offering Internships

- Networking opportunities and

- Making them conscious that language is important but not integral to survive. English was described as being a symbolic asset in many settings.

Helen Spencer emphasised the importance of not blaming the individual and assessing the intercultural competence of individual employees.

English was a symbolic asset for my mother. When she was 17 she arrived in Australia. Within 2 weeks she secured employment on a production line. Her friend who got her a job said to her, if anyone asks you How old you are? make sure you say 18. My mother and her friend even role played the question and answer.

Anyway, the supervisor came up to her and asked her, How old are you? Eighteen she replied. Every day, and sometimes twice a day he would come up to her. How old are you? Eighteen. Two and half years later, he was still asking her the same question. How old are you? My mother as usual would reply with a big smile 18.

The reality was that the supervisor was not asking my mother HOW OLD ARE YOU but HOW ARE YOU?

Now, to someone who doesn’t speak a word of English you can imagine how similar sounding How are you (ocker voice) and how old are you actually are. How are you, how old are you?

I wonder just how many chuckles that supervisor had every time he went back to the office. Perhaps my mother has been mythologised over dinner settings – “I had this woman who worked for me for almost three years and every time I saw her, I asked her How are you? she would reply with the number 18”.

Even today, my mother, barely speaks a few words of English. Yes, English is a symbolic asset for her.

Eugenia Arvanitis and Helen Spencer both highlighted the strong narrative of home and one that should not be imposed on refugees and migrants. I draw your attention to the 3 poignant images from Eugenia’s presentation depicting the tragic journey of a child refugee who all they hope for is a sense of belonging. A home.

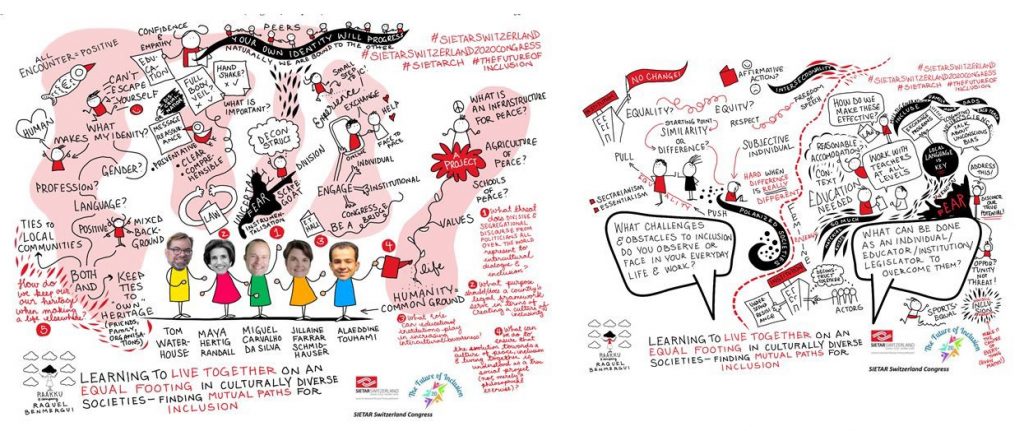

Learning to Live Together on an Equal Footing in Culturally Diverse Societies

I pay tribute to our Visual Harvester, Rebecca who so eloquently captures the sentiment of so many of the sessions and in particular questions that we all seek answers to. In the session titled “Learning to Live Together on an Equal Footing in Culturally Diverse Societies” and facilitated by Tom Waterhouse, the message that came through was that we all need to send a clear message to those engaged in hate crimes, hate speech and exclusionary practices, in particular during the pandemic where scapegoating is rife.

There was an emphasis on the role that education plays in bringing about openness and reducing racism which Miguel Carvalho Da Silva describes as the instrumentalisation of fear. Simply put, Miguel states, education allows us to deconstruct the instrumentalisation of fear.

Alleddine Touhami emphasizes we need to explore the common ground that binds us and that we need cultures of peace – the economy of peace, infrastructure of peace and to extend this to every aspect of society. I will come to the notion of peace later in my discussion.

In this session, we also heard the argument of equality vs equity and how we could look towards societies such as Canada through their policy of reasonable accommodation of cultural practices.

How do we strive to develop a spirit of openness and how do we better understand the root causes to the resistance to change in our society? – resistance which hinders the process towards building resilient communities in times of economic austerity. Touhami’s comment that every civilization has always existed because of the other resonated with me and leads me to the next slide.

Bilingual Coin – Peter Mousaferiadis

The image of the right was taken of me at one of the great musueums of the world, the Lahore Musuem. In the background is a Greco-Buddhist statue which was the inspiration for my moustache.

In 2016, I was appointed the Chair of the Lahore International Conference on Culture in Pakistan. Pakistan along with Afghanistan are often considered the cradle of civilizations. I like to refer to them as the Cradle of Worldviews.

In 326 BCE, Alexander lay the foundations to the Silk Road. He expanded his empire all the way throughout Central Asia and North of South Asia. When Alexander and his armies arrived in South Asia, the majority of them were polytheists. Generations later, many Greeks who remained there converted to Buddhism. They became the upholders and protectorates of Buddhism.

There was a fierce Greco-Bactrian King in the second century BCE who conquered more cities than Alexander. His name was Menandros or as others know him, Menander or Melinda.

Menandros heard stories about a Buddhist Sage called Nagasena. Nagasena had an answer to the deepest of philosophical questions in the Universe. Menandros became fearful of Nagasena. Eventually, Menandros plucked up enough courage to meet Nagasena. With his gold chariot and 500 horsemen he arrives at this quaint temple where Nagasena was quietly sitting.

What unfolded was a conversation which today has been immortalised and known as the Questions of King Menandros. Today this book has become the most important book after the Tripitika in Theravada Buddhism. Mendandros after his profound experience with Nagasena gave up his empire to his wife Agathoclea and decided to dedicate the rest of his life to Buddhism. What emerged was the Greco-Buddhist period and an empire full of interreligious and Intercultural centres.

When I first saw this bilingual coin I was awestruck at what it said about a society of 2000 years ago. A society that did not approach everything from an ethnocentric perspective and valued inclusiveness.

And here are two images of my visit to Taxila located at the crucial junction between South and Central Asia. Taxila was considered one of the intellectual capitals of the world for almost 700 years where humans of all faiths and religions lived in peace and mutual respect. It was known for having one of the first universities in the world dating back to the 5th Century BC. Students would travel huge distances to study at Taxila similar to students travelling to every corner of the globe today. Around 180BC King Demetrius the first redesigned Taxila so it could become a place that all people groups could congregate.

What you see before you on the left is the remains of a Buddhist temple. The temples carved on the bottom represent the Greek, Indo-Greek and Parthian temples. Did this mean all Greeks, Indians and Persians attended this place of worship simultaneously? “Yes!” according to my tour guide. “Jains, Christians, Zoroastrians, Buddhist, Hindus, Polytheists and Animists co-existed peacefully. This was a peaceful, interreligious and multicultural society until the White Huns came along and wiped Taxila away during the 5th Century.

I often wonder why we don’t reflect more on the past and study how societies lived at their best and more importantly what brought their demise about. And the image on the right is a statue of Aphrodite in the Taxila museum. My partner is called Aphrodite. It’s amazing that even when I am travelling 4 to 5 months a year to many parts of the globe I can never seem to get away from her.

What did that nexus and the creative process look like during this period?

Dr Ingunn Ness and Dr Vlad Glaveanu’s outstanding presentation whilst it dovetailed into the Future of Inclusion theme may also tell us of the process that took place 2000 years ago. Vlad highlighted how difference is essential to creativity. Creativity is the process that thrives on differences and creates spaces and environments which increase inclusion.

If we want to develop inclusive societies then we don’t need to look too far. We look to the past and the stories the past can share with us. I highlighted this in my Culture@theheartofEducation session last month. History tells us again and again, that all objects reinforce the notion that we are all interconnected. It’s these stories we need to tell; that cultures are not exclusive, not static and ever evolving and that the lifeblood of culture is confluence.

I was impressed with Vlad’s presentation, so much, I intend to have this research feed into my own work. As a creative and artistic director of more than 700 major productions over 3 decades, I have never understood the creative process in this academic and nuanced sense. I now know of the four personality types that characterise the creative process, radical oriented vs control and challenger vs driver roles.

Now, I completely understand why there is a natural resistance to change. Thank you Vlad.

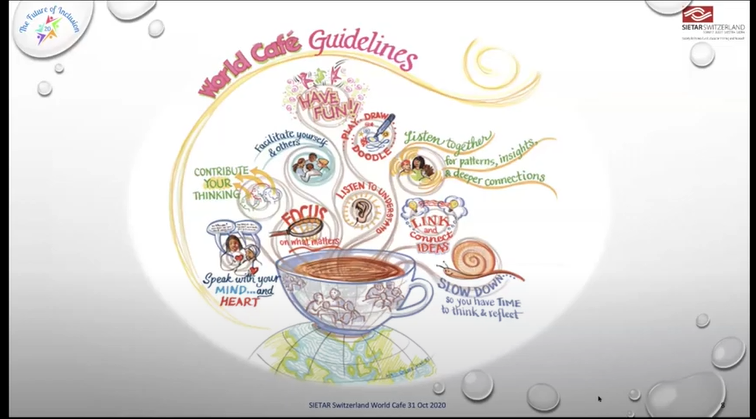

World Cafe

In just under three hours at the World Café, a 12 page document flurried with ideas of how we might be able to build a culture of peace for inclusive and pacific societies. The sessions were facilitated by Vincent Merk, Yassine Nasser and Gundhild Hoenig who inspired us to collaborate and discuss ideas to meet the Sustainable Development Goal No 16, Promote just, peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.

Yasser drew upon his heritage and the concept of UBUNTU and how that might be able to frame our approach to peace. UBUNTU – I AM BECAUSE WE ARE AND THE ANAOLOGY OF THE CHROMATIC Circle puts all complementary points of color at equal distance from the center and emphasises that we need each other, and that every point of view is required to understand totality.

Culture of peace requires partnerships and a win win. YASSER also shared with us, the Chinese word for crisis which is described by two ideograms which jointly mean ‘danger’ and ‘opportunity” and went on to illustrate the point that conflict is an opportunity for transformation. Yasser went on to say that we need to draw inspiration from nature to create circular organisation systems that rely on synergy as the foundation of all relationships.

Wanah Immanuel Bumakor told us that conflict is natural and that we need to be open to conflict because it provides the opportunity to collaborate. When we listen with intent, and are mindful of each other’s realities, conflict becomes transformational.

Building wellbeing is an ongoing process because societies are forever evolving. Wellbeing is often viewed in health terms however Vincent Merk pointed out that wellbeing is a much broader concept and should be viewed as how the individual and society can learn to be resistant to stress.

Bumakor in his talk presented the concept of peace and the difficulty with defining it and how history teaches us that at various points of time, peace has had a different meaning. Bumakor frames peace in how it has a lot to do with the change of the status quo, between the haves and the have nots. Bumakor tells us, and I quote, “Here lies the fundamental difference; the change of the status quo will be advantageous to one and not the other because one side sees change as an opportunity and the other side sees it as a threat”.

I’d like to share another story of the concept of peace and how looking towards the past might provide further insights into how we approach our work.

The Greek word for Peace

Something very monumental took place more than 2000 years ago in Central and South Asia. The notion of peace shifted from one of measurement to a more abstract concept. Ancient Greeks were into measuring everything – pi, fi, thita and so on. Everything was down to the infinite number and what couldn’t be measured was considered part of the metaphysics.

The notion of peace in Greek Antiquity prior to 300BC in my opinion underwent a major transformation. It went from a more tangible concept of measurement to becoming more abstract. The Greeks in Central and South Asia were introduced to the Hindu (Shanti) and Buddhist notions of Peace (state of mind). During this period, there was a massive convergence of Hellenic, Buddhist and Hindu thought. Philosophers were brought over to Europe from South and Central Asia and in many ways the groundwork was now being laid for Christianity.

So there are several points I am trying to highlight here. In the work we are all involved in, we need to think of the following:

- The meanings that cultures ascribe to language strongly depends on the linguistic, social, historical and cultural context.

- The meaning of words are forever changing and have different meanings depending on their contexts

- And let’s not ignore history.

The future also lies in our past. Ειρήνη (greek word for peace) is derived from Ειρω (eiro) which means:

- To string together all the essential components into one, into a state of equilibrium and/or

- To bring everything together which has been separated or divided.

The word “wreath” in ancient Greek is Ειρεσιωνη (eiresioni) , a derivative from the Greek word ‘eiro’ and σιώ (σιο) translating to ‘for God’. The εἰρεσιώνη (wreath) was often made from an olive branch. The wreath is a symbol for peace and adopted by major agencies such as the UN for their logo. The Greeks all along peace required many different aspects of working in harmony.

According to the Global Peace Index. Peace is the attitudes, institutions and structures that help encourage and sustain a peaceful society. Developed by philanthropist Stephen Killelea this tries to understand peace as the attitudes, institutions and structures that help encourage and sustain a peaceful society.

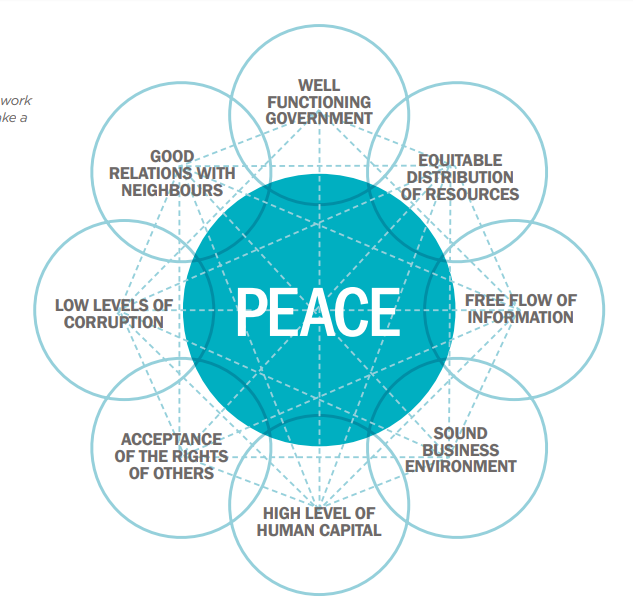

The Pillars of Peace is a holistic framework which describes the factors which make a country more peaceful. There is a strong correlation between the ancient concept of peace in Greece and the Global Peace Index which has identified 24 indicators underpinned by 8 pillars which make up peaceful societies.

Peace is a delicate concept which requires work. It does not come naturally. One pillar becomes weak and immediately the equilibrium of the peaceful societies we strive to create are disturbed. In a traditional sense, Peace can often be described as the absence of violence or conflict. Moving from a culture of conflict and violence to a culture of peace to live a virtuous economy of human relationships

In the World Café session facilitated by Gunhild Hoenig resulted in a harvesting document we all contributed to. “Conflict” appeared 17 times by participants in response to the question:

What is the leverage of actions to transform or prevent conflict in order to maintain an inclusive climate? Here are a few instances of the use of the word conflict:

“Remember most conflicts are born from misunderstanding not a desire of conflict, and most people want to find a resolution”

“How we portray and frame conflict is key – we can use conflict to bring out the best in people and organizations”

“Education is key in preventing conflicts”

“It is during conflict situations that creative solutions can be found if intercultural communication skills facilitate the process”.

“Understand the real source of conflict”

Google as a Social Barometer

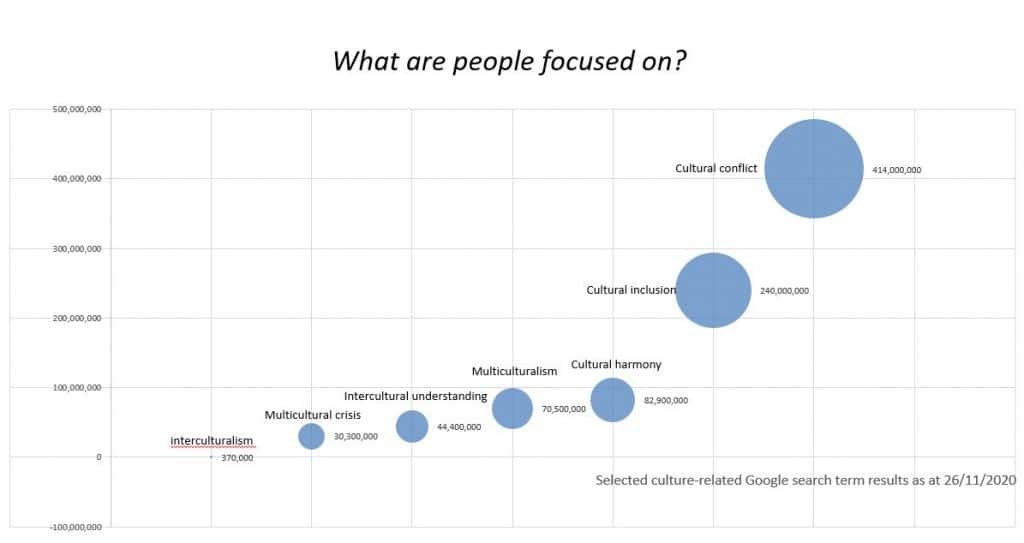

One of the ways to look at how important things are is to look for the volume of appearances on the WWW for key terms. I typed in some key search terms and this is what I noticed around different types of words connected with culture.

Interculturalism, Multicultural crisis, Intercultural Understanding, Multiculturalism, Cultural Harmony, Cultural Inclusion and Cultural Conflict. The volume of pages connected with Cultural Conflict was exponentially greater than Interculturalism, the space we all work in. What does this tell us?

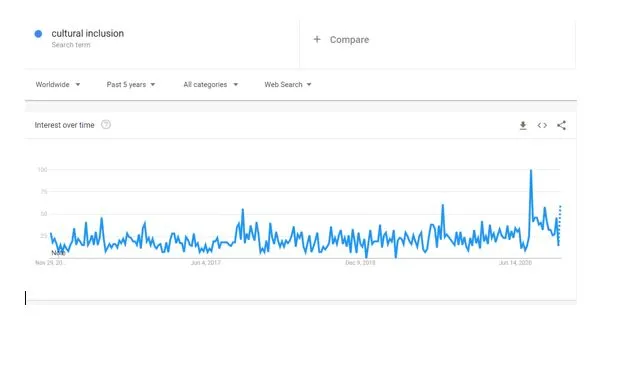

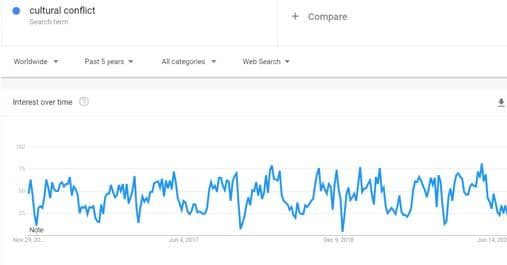

In the trends slide, you can see 2 major spikes across cultural inclusion and cultural conflict. Note the period when these spikes took place. After the first wave in Europe when Corona virus cases had subsided and before the exponential increase.

What do you think the reason is for this sudden spike in the middle of the first two major waves? Please feel free to share your thoughts in the Chat Box.

Global Peace Index

75% of all conflict in the world has a cultural dimension. Bridging the gap between cultures is urgent and necessary for peace, stability and development.

In 2019, the cost of violence equates to more than 10.6% of the world’s GDP. This represents a mind-blowing and staggering figure of 14.5 trillion dollars or $1,909 per person.

According to UNESCO 75% of all conflict in the world has a cultural dimension. Bridging the gap between cultures is urgent and necessary for peace, stability and development. Just makes logical sense for me that we need to be investing more in this area.

Pillars of Sustainability

We operate at the point where these Pillars intersect.

“Culture is both ‘overarching and underpinning’” – J.Hawkes, The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability (2001)

In this venn diagram, I am illustrating how in public planning, culture should be given equal footing to economic, environmental and social planning.

A colleague of mine, John Hawkes, highlights in his book, The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability that culture is overarching and underpinning. 20 years on from Jon Hawke’s book, my country Australia is yet to have a Ministry for Culture.

Every society has a culture. A way of thinking. A way of behaving. Social Norms. All these guide society. If you want to have social change then you need to change culture; in other words, social change is embedded in cultural change. Throughout the conference there was no shortage of ideas and existing practice and examples of what we can all do.

In Unpacking Migration part 2 we heard of various non-government organisations and their efforts to go beyond integrating to including migrants into society, in another words, accepting them for who they are.

This reminded me of my work in the mid-90s when I was the Artistic Director of the Orana Chamber Orchestra which was dedicated to supporting and staging concerts with orchestral musicians from the former Soviet Union. The Orchestra’s objectives included featuring outstanding musicians who then went on to work with our major orchestras however it’s deeper role was as described in the SIETAR Congress “to counter the xenophobic and anti-immigration discourse around migrants” who were coming to Australia from the former Soviet Union. And mind you, there was a lot of it at the time.

Today, it is being directed to those who have come to Australia from the Middle East, Africa, South Asians and most recently because of the pandemic, East Asians.

Learning to live together on an equal footing in culturally diverse societies – Finding mutual paths

In the image before you by Monika Ernst a congress delegate, Monika perfectly captures the theme of the conference ‘the Future of Inclusion” because it calls upon us, to act, and that the road to understanding and peace requires efforts from all of us. It is not one sided. It’s reciprocal. It requires us to take on other perspectives and include them in the building of bridges.

I’d like you to think of yourself as a bridge builder and what this means to you. What will be your takeaways from this congress? Please share some of your ideas in the chat box. I want you to think about where were you before this conference and where are you now. And lastly, how the skills and knowledge you have acquired be extended and more importantly transferred to other areas.

Final Thought – 13.9 Billion Years Old

In the beginning of 2006, I came up with the theme of The Big Bang: Creations Stories of the World for the 2007 Australia Day Concert. In October of that year John Mather and George Smoot were awarded the Nobel Prize for pinpointing exactly when the Big Bang took place.

But around the same time there was another discovery. John Cramer, an acousticphysicists, prompted by his son with the incessant repetition of Dad Dad Dad what did the Big Bang Sound Like? Cramer was able to now work out with the data available to him the exact sound of the Big Bang. I am sorry to disappoint you. The Big Bang was not the mother of all explosions but rather like a hum. During the research phase as Creative Director of this Australia Day Concert we discovered that there were many cultures including the first nation cultures of Australia which describe the Hum at the very beginning of time, the source from which all things come from.

But George Simonovich known to many of us as George Simon who has worked in 60 countries creating games which bring people together in safe spaces, would see this image before you and would probably be asking “what crack was it that gave the universe its light”.

My interpretation is not based on that told to me more than 40 years ago by a science teacher who said that the Universe was 4 billion years old but rather a more philosophical approach. An approach that marvels at the Universe which has been around for 13.9 billion years and came into existence for us to share this very special moment.

I ponder. What created this remote chance, which allowed for light to come through a crack and for us to be here today? In the spirit of humility, compassion and camaraderie, I now call upon us to act out the African proverb that Migration Expert Papa Balla Ndong shared with us – Ben Loho Du Taju which translates as

“One hand cannot clap, it takes 2 hands to clap”.

Peter Mousaferiadis is available for key note addresses, roundtable discussions and other speaking engagements. Please contact us to enquire or to book.

Share this Post